Ever get the feeling that you as a manager or your company’s managers are driving variability and chaos in your company through uncertain decisions and conflicting goals? You’re not alone. The Vice President of Manufacturing of a multi-billion company once reported that Production had done a fantastic job implementing Lean Manufacturing to reduce cycle times but there was too much inventory in assembly stores (production fed assembly stores). What the VP didn’t report was that he had loaded the MRP system with 130% more demand than the company had ever demonstrated it could produce. What we line managers knew was that war room meetings were a weekly, sometimes daily, occurrence and we were constantly expediting parts.

Executive management is often a major driver of company chaos. Ever seen whack-a-mole management? For example, Q1 we’re working on customer service, “Lay in inventory, don’t miss shipments!” to Q4 we have to reduce cost and make revenue, “Cut inventory and ship whatever we can to make the numbers!” (See pp.25-27 in Factory Physics for Managers for more discussion) Is this because managers are trying to create chaos? There are some executives who are pathologically driven to mix things up but I think that most managers are well-meaning and would prefer less chaos than more. Over 30 years in operations management and consulting, I’ve seen repeated patterns of self-inflicted management pain—most of which are avoidable. Following are three ways to inoculate an organization against much self-inflicted pain.

1) Education – There is an incredible amount of misinformation surrounding operations management. The widespread lack of understanding of basic scientific operations relationships among experienced managers beggars belief. This problem is easily remedied. No, you and your managers don’t have to go to college and get a degree. There are many simple illustrations and exercises that can be used to provide executives and managers with a better understanding of the natural science of their business. There are a few basic relationships anyone managing any kind of operations MUST understand:

Trying to run a business without understanding these relationships is like walking along a high cliff without understanding the law of gravity. Sure, you may stay on the path along the cliff by chance and reach your destination safely. Without an understanding of the dire consequences, you may also choose to walk off the cliff. Some examples of walking off the cliff in operations:

From Tony Del Sesto, Director of Manufacturing Research and Development at DMDII, a couple of ways to walk off the cliff with digital technology:

For quickest reliable education on practical operations science, see Factory Physics for Managers or attend a Factory Physics seminar. If a more academic approach is desired, check out the award-winning Factory Physics textbook. If you want to push the boundaries of operations science, check out Of Physics and Factory Physics.

2) Manage to a performance envelope

Don’t try to plan and manage deterministically—which is the way MRP/ERP systems are built. Your organization’s performance depends on the range of demand you attempt to meet and the range of your (and your suppliers’) response to demand. This range of demand and supply is what I call a performance envelope. Managers can NOT predict what demand they will see, for example, a week from Tuesday at 2PM. Forecast accuracy generally is bad and it’s bad the further out you try to forecast. Rather than trying to predict demand or attempt perfect forecasting, determine the range of demand you will target—a much easier task.Here’s a demand example of a performance envelope: are you going to plan for a demand of 10 per month +20 to -20 or 100 per month +50 to -10? For a performance envelope example on the supply side, your own production or suppliers or both: are you planning on a lead time of 3 weeks with variation of 2 days late to 1 day early or will the anticipated lead time be 8 weeks with variation of 1 week late to 1 week early?

Setting a performance envelope enables a scientific calculation of the resources and policies (more on policies in item 3) needed to meet the anticipated demand range within the expected response time. It’s entirely predictable.

As it turns out, most MRP/ERP systems can be configured to work with the performance envelope approach. Success hinges on understanding the natural science of your operations and then using the technology to work with that science. Too often, managers and executives buy expensive technology and then use the technology for simple book keeping—variability is handled with extensive expediting and war room meetings.

Set goals based on a performance “envelope” of demand and supply. The science of operations then will enable you to determine what resources (cost) you will need to meet expected range of demand and supply.

3) Connect Executive Strategy to Policy Execution

Executives usually set organizational goals based on financial performance aspirations. Often these aspirations are not grounded in a scientific understanding of the organization’s capability to achieve them. (See example in first paragraph) Regardless, the aspirations are translated to goals and published to the organization. There are then “a thousand points of light” (company employees) trying to achieve the company goals through their own individual interpretation. As a result, the company IT system becomes a really expensive bookkeeping system to track where each order is and what each employee is doing. The IT system bears little resemblance to a control system monitoring control limits and directing executives to take action when performance and/or policies (on-time delivery, inventory position, throughput, WIP levels) are out of their required ranges.

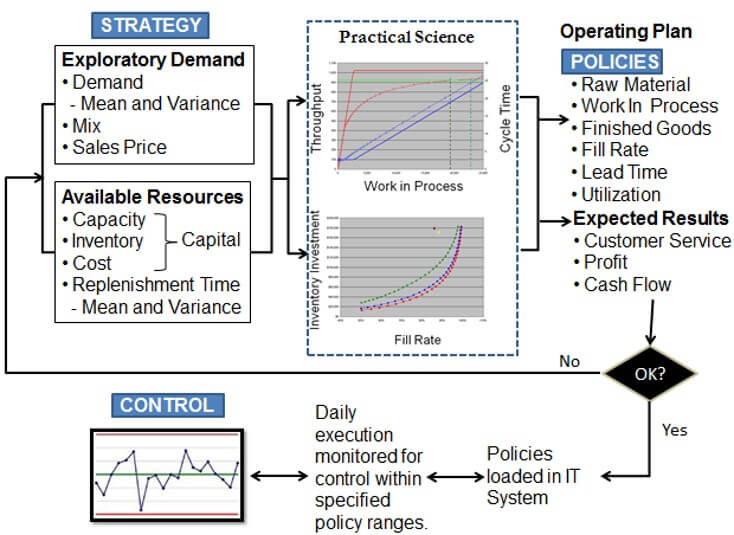

A powerful antidote for self-inflicted chaos is for executives and managers to base their goals on a scientific evaluation of the organization’s capability to respond. This understanding provides a set of policies that the organization is capable of executing. Note, the approach requires working to a performance envelope as described in item 2. Once executives have determined a feasible performance envelope for their organization, required policies for execution include:

The policies are entered into the planning system and there is weekly or daily review to determine if the policies are being followed. If the policies are followed and the performance envelope is accurate, the organization will achieve its financial and customer service goals. See illustration of the process in the figure below.

If results are not as expected, there are only three things to check:

This approach makes management easier and proactive since managers are looking for policies that are not being executed rather than getting lost in the complexity of tracking each individual product shipment or service delivery. The manager relies on individual employees closest to the product or service to handle day to day variations.

This approach makes management easier and proactive since managers are looking for policies that are not being executed rather than getting lost in the complexity of tracking each individual product shipment or service delivery. The manager relies on individual employees closest to the product or service to handle day to day variations.

Management decisions often lead to self-inflicted chaos in an organization. Hopefully, the ideas provided here will help your organization avoid self-induced variability and improve your ability to manage your environment more easily and with better results.

Do you have any examples of self-induced variability and your solutions? Please let us know, comment below. For more information on how to apply the powerful, practical operations science of Factory Physics concepts to your organization, contact us at info@factoryphysics.com or call me at 979.846.7828 extension 151.

Ed Pound is Chief Operations Officer of Factory Physics Inc. Ed has worked with major international companies such as Intel, 3M, Baxter Healthcare and Whirlpool providing education and consulting in the practical operations science of Factory Physics concepts. Ed’s work has helped companies realize millions of dollars in improvements and make operations, supply chain management and product development easier. Ed is lead author, along with Dr. Mark Spearman and Jeff Bell, of McGraw-Hill’s lead business title Factory Physics for Managers.